Intelligent design is not a scientific theory for several reasons.

1) Any scientific theory must falsifiable. This means that it has to be something that can be tested and proven wrong if it is indeed wrong. There is no means of doing this with the "theory" of intelligent design.

2) Any scientific theory must be parsimonious, in the sense that it must be the simplest and most realistic explanation. Now, I know that many people might say that it doesn't get more simple than saying "God created everything." However, based on scientific observation, does it seem more probable that the universe and all living things were spontaneously generated at once or that modern life is the result of the processes of natural selection and random mutation over the last three billion years? We can rule out the first simply by the chemical law that mass and energy are neither created nor destroyed (although they may be interchanged). The second possibility is supported by mounds of empirical evidence.

3) Any scientific theory should allow you to make predictions. With evolution, you can do this; with intelligent design, you cannot.

4) Any evidence must be reproduceable. There are countless experiments testing the tenets of evolutionary theory; for example, you could test random mutation by inducing mutation in yeast with UV radiation (the same radiation that comes from our sun) and observing the phenotypic variation after plating these samples and allowing colonies to grow. Likewise, you can induce mutation in more advanced animals and observing the phenotypic effects of those mutations. The results of these tests will be consistent over time. The other bases of evolution are quite testable and reproducable as well.

Anyway, I've seen plenty of people claim that evolution and intelligent design are equally viable scientific theories, but intelligent design does not meet the qualifications to be considered a scientific theory.

My question is: how do people still want to call ID a scientific theory and teach it alongside evolution when one is faith and the other is a true scientific theory?

Why Intelligent Design Isn't a Scientific Theory

Moderator: Moderators

- Jester

- Prodigy

- Posts: 4214

- Joined: Sun May 07, 2006 2:36 pm

- Location: Seoul, South Korea

- Been thanked: 1 time

- Contact:

Post #81

Of course it does not, we get to that further down.goat wrote:Of course, this does not address the issue that "I.D." does not make predictions, does not have any way to test for it, and does not explain the complexity of life as we see it, except to say 'An intelligent designer (wink wink god) did it'.Jester wrote:This does not discredit my basic point, that scientists on all sides of this (and every) debate are emotionally attached to their theories and come in with prejudices. I do not deny that the creationists and the ID supporters have such prejudices. I feel, however, that it is dangerous to assume that the proponents of evolution/origin of life theory and other naturalistic explanations do not have similar attitudes.

For the record, I am not a proponent of ID; I merely had questions about it. And, personally, I despise the “God of the gaps” reasoning. I have never and will never use that apologetic.

As for predictions of ID, those of which I am aware are as follows:

Life will be shown to lack a steady pattern of gradual increases in complexity

Basic life will be shown to have developed relatively quickly.

Basic agreement there.goat wrote:I will agree with you about abiogenesis. However, it is much more on the hypothoses stage than I.D. is. There are several competing ideas that CAN be theoritically tested about how the first replicating molecules came into existance.

I don’t think we can give evolution that high a title, but I suppose that is beside the point.goat wrote:On the other hand, you vastly understate the evidence for evolution. It has made many strong predictions that have been validated (antibodic resistant bacteria for one). It is probably the best understood and most highly tested from any scientific theory we have.

More directly, while the “God in the gaps” argument is a logical fallacy, the misguided creationists who have been promulgating it have come up with some legitimate problems (not all of them, mind you, but there is a real concern). Macroevolution is not nearly so well explained by natural selection as once believed.

At the risk of redundancy, let me say again that none of this really proves/disproves the existence of a supernatural world. Curiosity aside, my main reason for getting involved was to gain some factual information and realistic perspective on ID before it came up among a Christian group (where my opinions generally have much more weight, giving me much more responsibility to be correct, than on this site).

- Jester

- Prodigy

- Posts: 4214

- Joined: Sun May 07, 2006 2:36 pm

- Location: Seoul, South Korea

- Been thanked: 1 time

- Contact:

Post #82

I’d be happy. I’m always grateful for your opinion.Confused wrote:While posted to Jose, I would like to add a few things as well if you don't mind:

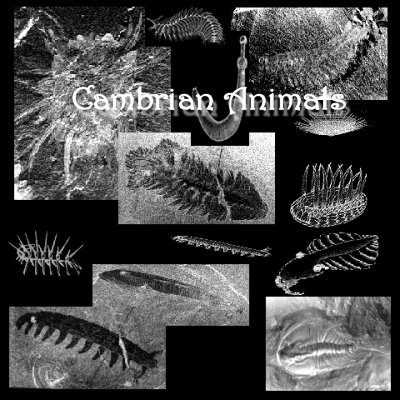

I have heard the concept of growing complexity in several places. Jose has mentioned it, as has some of my casual reading (and I think my biology textbooks, though I’m not sure). I’m not claiming to have proof on this, but that is supposed to be the general pattern of evolution as far as I know. The ‘most complex phyla’ is Chordata (I believe that is the correct spelling), of which humans (all vertebrates) are part.Confused wrote:Which most complex phyla are you referring to. Evolution postulates that species will evolve in a form that makes it a positive adaptation for survival in an environment. In some cases, this may seem as if we are taking a complex organ and simplifying it for a new environment. For example: the appendix. We needed it initally due to the average diet of early man consisting of vegetarian foods. As we now rely less on vegetables as the staple of our diet, and more on meat, the appendix doesn't serve much of a purpose. Evolution would hypothesize that at some point the human body will no longer contain one, it will phase out.1. What do you think of the fact that the evolutionary stance makes the prediction that life should grow in complexity over time, but that the most complex phyla is found in the Cambrian period, rather than being a later development?

The size of the body is not directly important, it is merely that smaller animals have shorter lifespans (and, consequently, more generations and more evolution). I did not know this rule of allopatric speciation. Is the smaller population really more helpful in spite of the fact that there would be more mutations in a large group? I don’t claim to know, but it would be a definite mind-bender for me.Confused wrote:I will take a stab at this, the larger the population involved, the slower evolution will occur because of the larger gene pool. The smaller the population, and the more isolated it is, the more narrow the gene pool, so the rate of evolution will actually be faster. It is allopatric speciation. Though I am not sure how the size of the bodied animal plays into it.2. Would you give me a comment on this quotation?: “A naturalistic model would predict a multitude of transitional forms among tiny- bodied, simple life-forms, vastly outnumbering those among large-bodied, complex life.” It is based on the claim that shorter life span and larger populations should increase the rate of evolution in smaller bodied animals, but that the fossil record shows the opposite.

Thank you. I appreciated the information (wanted to see if it matched up with my other sources. Is it true that the earliest single cellular life formed in less than 100 million years? I’ve seen that a couple of times, but it does seem to be fast based on our current understanding.Confused wrote:It depends on what life you are referring to…3. General question: What is the age of life on Earth, according to what you have read?

Again, thank you.

- Goat

- Site Supporter

- Posts: 24999

- Joined: Fri Jul 21, 2006 6:09 pm

- Has thanked: 25 times

- Been thanked: 207 times

Post #83

You don't seem to understand that 'macroevolution' is merely the accumunlation of a whole bunch of smaller changes. The key here is that mutations are accumulative. Over time, there are more and more changes in populations, and different set of allees will become dominate. This explains all the diversity we have for life. You might reject that evidence, but it the evidence is quite strong never the less.Jester wrote:Of course it does not, we get to that further down.goat wrote:Of course, this does not address the issue that "I.D." does not make predictions, does not have any way to test for it, and does not explain the complexity of life as we see it, except to say 'An intelligent designer (wink wink god) did it'.Jester wrote:This does not discredit my basic point, that scientists on all sides of this (and every) debate are emotionally attached to their theories and come in with prejudices. I do not deny that the creationists and the ID supporters have such prejudices. I feel, however, that it is dangerous to assume that the proponents of evolution/origin of life theory and other naturalistic explanations do not have similar attitudes.

For the record, I am not a proponent of ID; I merely had questions about it. And, personally, I despise the “God of the gaps” reasoning. I have never and will never use that apologetic.

As for predictions of ID, those of which I am aware are as follows:

Life will be shown to lack a steady pattern of gradual increases in complexity

Basic life will be shown to have developed relatively quickly.

Basic agreement there.goat wrote:I will agree with you about abiogenesis. However, it is much more on the hypothoses stage than I.D. is. There are several competing ideas that CAN be theoritically tested about how the first replicating molecules came into existance.

I don’t think we can give evolution that high a title, but I suppose that is beside the point.goat wrote:On the other hand, you vastly understate the evidence for evolution. It has made many strong predictions that have been validated (antibodic resistant bacteria for one). It is probably the best understood and most highly tested from any scientific theory we have.

More directly, while the “God in the gaps” argument is a logical fallacy, the misguided creationists who have been promulgating it have come up with some legitimate problems (not all of them, mind you, but there is a real concern). Macroevolution is not nearly so well explained by natural selection as once believed.

At the risk of redundancy, let me say again that none of this really proves/disproves the existence of a supernatural world. Curiosity aside, my main reason for getting involved was to gain some factual information and realistic perspective on ID before it came up among a Christian group (where my opinions generally have much more weight, giving me much more responsibility to be correct, than on this site).

Post #84

Jester:

A larger population has a larger gene pool to mix with, a smaller and isolated population has less of a gene pool to mix with. As you know, the closer to ones relation one is when reproducing, the increased likihood of mutaions, some beneficial, some lethal, and some insignificant, increases. The allopatric speication says just the opposite of what you say. It says we will see more mutations (evolution) in smaller and isolated groups and they will occur faster than those of a larger more open population because of the gene pool and the adaptation of the species.The size of the body is not directly important, it is merely that smaller animals have shorter lifespans (and, consequently, more generations and more evolution). I did not know this rule of allopatric speciation. Is the smaller population really more helpful in spite of the fact that there would be more mutations in a large group? I don’t claim to know, but it would be a definite mind-bender for me.

What we do for ourselves dies with us,

What we do for others and the world remains

and is immortal.

-Albert Pine

Never be bullied into silence.

Never allow yourself to be made a victim.

Accept no one persons definition of your life; define yourself.

-Harvey Fierstein

What we do for others and the world remains

and is immortal.

-Albert Pine

Never be bullied into silence.

Never allow yourself to be made a victim.

Accept no one persons definition of your life; define yourself.

-Harvey Fierstein

Post #85

You are quite right--scientists of all flavors tend to be personally attached to the ideas that they have developed themselves. There are also very strong societal and cultural contexts that channel people's interpretations along certain directions. It can be argued that evolutionary theory has been around for so many generations now that it is "a given," and channels scientists' thinking.Jester wrote:This does not discredit my basic point, that scientists on all sides of this (and every) debate are emotionally attached to their theories and come in with prejudices. I do not deny that the creationists and the ID supporters have such prejudices. I feel, however, that it is dangerous to assume that the proponents of evolution/origin of life theory and other naturalistic explanations do not have similar attitudes.

If we look historically, however, it may help. Evolutionary theory grew out of Natural Theology--the idea that if we catalog everything on Earth, we can better recognize the glory of god. It turned out that the more people learned, the more they found that was at odds with the simple interpretation of Genesis...and eventually, evolution was proposed to explain the data. There was resistance, but in the end, scientists were forced by the weight of the evidence to abandon their prior explanations and accept evolution. Unfortunately (in a way), those struggles are in the distant past, so the public tends to view evolution as a form of scientific bias rather than a principle that is so strongly confirmed that there's no need to discuss it any more.

Indeed, there are some biochemical reactions that require light of one or another wavelength. For the most part, though, UV is damaging--it is absorbed by chemicals containing double bonds, and can cause the bonds to break and the molecules to rearrange. Both proteins and DNA are subject to this kind of damage. It's not good.Jester wrote:I have read that, while some frequencies of ultraviolet light radiation aid certain biotic processes, the full radiation spectrum in sunlight is harmful to life, particularly as delicate a biotic situation as the formation of early cells. This is typically not a problem, due to the ozone layer of the upper atmosphere. However, the presence of oxygen has been shown to nullify the Miller-Urey experiment. Have you personally heard anything that would explain how life might have formed in spite of this problem?

So your question is important. There was lots more UV hitting the earth before photosynthesis produced enough oxygen to build up an ozone layer. How, then, could amino acids and nucleotides get produced, and why weren't they all destroyed?

The short answer is: every rock has an underside. A longer answer is: a place like Yellowstone has lots of cracks and fissures, and lots of sulfur, and lots of places where warm water evaporates to leave concentrated goo from whatever was dissolved in it. The appropriate image to visualize for a chemical origin of life is probably something like the edge of a pool, with perhaps a bit of sulfur around, and some cracks and fissures that UV light cannot penetrate. (I mention sulfur simply because some micrororganisms use H2S rather than H2O as a source of electrons--"chemiautotrophs" rather than "photoautotrophs." A chemical energy source is likely to pre-date the development of a means of harvesting light energy in normal photosynthesis. So far as I know, this is the current thinking.

Oh Boy!...this is the fun part.Jester wrote:Okay, I’ll check that one out. While I do, let me add a couple of more to the list.

Two things: first, evolution does not predict that things will increase in complexity. It merely predicts that things will change. The perception of an inexorable increase in complexity comes from three sources: first, complexity started at zero, and had no direction to go except up. Second, people like to think of themselves as god's special creations, superior to all other life; or, if they accept an evolutionary view, they fit it into "human specialness" by imagining themselves as being the most complex critters yet produced by evolution. Third, both biblical and evolutionary thinking were superimposed on the Greek's Great Chain of Being, which put pond scum at the bottom and humans at the top (with angels and gods in levels above the top).Jester wrote:1. What do you think of the fact that the evolutionary stance makes the prediction that life should grow in complexity over time, but that the most complex phyla is found in the Cambrian period, rather than being a later development?

The data show there is no rule concerning complexity. Species introduced to islands, and then tracked over time, are just as likely to lose complexity as to gain it. Steve Gould explored this issue in detail in Full House, in an amusing mix of biology and baseball.

What about the Cambrian? Well...

Not all of the fossils from the Cambrian are what I'd call representatives of the complex phyla we know today. Indeed, the earliest chordates are said to have been found in Cambrian exposures, but a "basal chordate" like a tunicate isn't quite what I'd call an example of a mammal, or even a fish.

Not only are the Cambrian fossils very different from what we see now, and clearly representatives of only the simplest precursors of current life, no one tends to mention the plants when they speak of the Cambrian Explosion as the time when all of the phyla appeared. There were some algae, but none of the traditional plant phyla were present. The plant phyla tend to appear one by one as we progress through geological time, with the flowering plants being quite recent indeed.

Let me draw a picture of three very different bacterial species, each more different from the others than plants are from animals: Ready? Here goes: . . . There. Three dots that look the same to us, but are biochemically very different. To make it more realistic, I'll redraw it with a bunch of fossils that illustrate some of the transitional forms: ...................................Jester wrote:2. Would you give me a comment on this quotation?: “A naturalistic model would predict a multitude of transitional forms among tiny- bodied, simple life-forms, vastly outnumbering those among large-bodied, complex life.” It is based on the claim that shorter life span and larger populations should increase the rate of evolution in smaller bodied animals, but that the fossil record shows the opposite.

Silly, I admit, but it makes my point.

Here's an interesting thing: most of us have the perception that evolutionary rate (i.e. mutation rate) should correlate with generation time. It turns out that it doesn't. Mutation rates tend to correlate with overall time. It's pretty similar for mammals, regardless of whether they are mice or humans. I think this tells us that the main source of mutations is not errors in DNA replication during normal cell division, but chemical damage to DNA. X-rays and chemical mutagens can induce mutations in fully-formed sperm cells of fruit flies, in which DNA replication has finished. (Drosophila geneticists do "mutant hunts" by mutagenizing males.) From what I've read, I think the most common mutagen is oxygen radicals.

So there are two things that make your quoted expectation unrealistic. First, the small, simple organisms are both similar to one another (bacteria) and hard to fossilize (worms, insects, etc). Bigger things with hard parts are easier to examine and more likely to fossilize, particularly if they live in water--like bivalves. It's hard to study things you can't find and can't distinguish even when you do find them.

The current estimates of earliest life seem to be around 3 billion years ago, based on things that look like bacterial fossils and chemical composition in rocks that is hard to explain by normal, abiotic geochemistry. But I can't answer your second question, other than to say "I guess it took as long as it took." There are too many unknowns. For example, if the asteroid hadn't crashed into Chixulub, wiping out the dinosaurs, we'd probably still be little furtive shrew-like critters trying to avoid being eaten.Jester wrote:3. General question: What is the age of life on Earth, according to what you have read? Also, what is a realistic time-frame for species evolving to the state they have reached today.

Fortunately, the bias can enter into the interpretation, but not into the data themselves. Data are really the only "facts" in science. We observe XXX. What do we make of it? The trick is to examine the data first, come to your own conclusion, and then check to see if the authors got it right.Jester wrote:My trouble is that I have come to believe that I will always be reading one bias or another. It sometimes feels that sifting through the biases is the only thing harder than sifting through the data.

This assumes a particular transitory phase. The proper question is "what was the transitory phase?" This question makes sense only in the context of the next question, "what was the ecological context in which these animals/plants lived?" Something half-way between a fin and a foot seems problematical if we think of your average shark walking up onto the beach. But it's not problematical when we know the ecological context from the other fossils found in the same locale, and realize that this guy lived in a swamp. If he used his fin/foot transitional structure to push against mangrove roots while still in the water, now there's a very good use for it.Jester wrote:My issue with microevolution explaining macroevolution is that there are many traits which are, admittedly, very genetically useful but would be worthless or a hindrance in its transitory phase. To that end, I would claim that, while there must be some scientific explanation of such developments, long-term microevolution driven by natural selection does not seem to be that explanation.

It never made sense to say that the water dried up, so fish had to walk to other ponds in order to survive. They'd have to wake up one day with feet. Well, now that we know the ecological context--swamps, not drying ponds--we can make much more sense of the data.

I agree that it seems wonky for any species to have a larval form, but many do. I'll have to say that I don't know what genes are controlled in what ways to account for this...but there are lots of molecular developmental biologists working on it, so I bet we'll get a better picture in the not-too-distant future.Jester wrote:I agree that this does account for some problems, but I am left with the issue of development of certain aspects (such as the caterpillar’s ability to become a butterfly involving several interdependent genes, not a process that could be explained through the force of natural selection) as well as the fact that the fossil record does not show the tree of life in the same way we have categorized it. There is an end to which we are classifying a species as older than another because it fits with this theory, which is perfectly acceptable if the theory has been shown to be true, but is definitely circular logic if we are trying to establish its truth.

As for the tree of life...The current best trees are based on DNA sequence similarities. Naturally, they can only include living species from which we can get DNA. Note an important fact about this sort of tree: all of the species are currently alive, and are equally far removed from the first life. They are all the same age.

There is a mis-perception of thinking that "primitive" mammals are "older species," or that pond scum is less-evolved than humans. We've all evolved the same length of time. Things that happen to look more like ancient things from the fossil record are probably things that happened to have a body plan that was really successful. Or, they lived in places where there wasn’t much competition.

Now, if you take a DNA-based tree and add onto it some extinct species (based on morphological characters), and superimpose it on a geological time scale, danged if you don't find that it all fits. There's a simple example here.

So, the scientific reasoning is not circular. What seems circular is the simplified description that is passed around in general conversation.

In this sense, I think the Dawkins types do their science a disservice. If he would stick to what we can really conclude, he'd be better. That is, we can conclude that we can explain the natural world through natural processes, and there is no absolute need for gods. Of course, there may be gods, but we have no data that allow us to say anything about them. Or, there may not be gods, but without data, we can't really tell.Jester wrote:I have always felt that this is the major point that both creation “scientists” and atheists who wish to use science to “disprove” the existence of the supernatural seem to miss.

The short answer: we don't know. I'll argue that nucleic acid components, even now, "tend to hydrolyze," and that RNA molecules are particularly prone to hydrolysis. By this logic, RNA shouldn't exist now, either. And, while there are chemicals that might react preferentially with nucleotides, it's rather hard to argue that these chemicals were always present with nucleotides. We know that different things are distributed unevenly around the earth now; why would they have been perfectly uniform then? Sure, one can argue that life was unlikely, but then, the probability is also vanishingly low that anyone would ever get the precise combination of my Mom's alleles and my Dad's alleles that I got. Yet, it did happen, likely or not.Jester wrote: “Many accounts of the origin of life assume that the spontaneous synthesis of a self-replicating nucleic acid could take place readily. Serious chemical obstacles exist, however, which make such an event extremely improbable. Prebiotic syntheses of adenine from HCN, of D,L-ribose from adenosine, and of adenosine from adenine and D-ribose have in fact been demonstrated. However these procedures use pure starting materials, afford poor yields, and are run under conditions which are not compatible with one another. Any nucleic acid components which were formed on the primitive earth would tend to hydrolyze by a number of pathways. Their polymerization would be inhibited by the presence of vast numbers of related substances which would react preferentially with them. It appears likely that nucleic acids were not formed by prebiotic routes, but are later products of evolution.”

Needless to say, any life that arises in particular conditions will be suited to those conditions. But, are there alternate possibilities? There are probably bazillions. There are an infinite number of possible amino acids; life happened to choose only 20. There are lots and lots of nucleotides; life happened to choose only 4. There are lots and lots of polymers that can be built from somewhat variable subunits, so there are lots and lots of potential information-carrying molecules. All of these molecules come in right-handed and left-handed forms, so it would be perfectly possible to have life that uses the opposite forms from what we happen to use. As it turned out, though, some individual self-reproducing thingie happened to use what it was made of, and it happened to be better at reproducing than were the other thingies around it. So, it out-competed the other things, and channeled subsequent evolution down the path it started. Every time something out-competes the challengers, there's another restriction in what changes can happen next.Jester wrote:My trouble is that this is back to a world of pure “we don’t know”, which is exactly where I started at. It seems that life is so specified to the forces of the universe in general and conditions of Earth in particular that it would be more logical to conclude that there were few, if any, possibilities for alternative forms of life. It would take a great deal of possibilities, however, to make the rise of complex life probable.

This relates to the Cambrian phyla, by the way. Once those primitive forms had arisen, they restricted the development of their descendents. There were enough of 'em, and they were successful enough, that new things tended to be out-competed by the guys already there.

If we think of a simple RNA, we can make some sense of this. Suppose it's a short sequence that can fold back on itself to make a little hairpin. This might enable it to form a template for replicating itself. But, it would be sloppy, and might put in an extra base. On the next round of replication, the extra base would be copied, and we'd have a hairpin that's one base-pair longer. It would be a little bit more stable. Mistakes that leave out a base would be less stable, and might not replicate as well.Jester wrote:I understand the idea that Nucleic acids grow over time, but do not understand what principal causes this increase in complexity before the creation of a cell which is subject to evolution. Thus, the probability of a simple strand of RNA for the earliest cells developing over time would not appear to be much (if at all) higher than the encoding of such a cell developing all at once.

Two molecules that have the ability to interact with each other can also form hybrids, or double-length molecules, or molecules with extra hairpins. The catalytic RNAs that we know all have multiple hairpins, so this seems like something that is likely to have happened.

The point is, a very simple self-replicating molecule (in a crevice, away from UV, with silica grains to act as catalyst) can grow into a more complex molecule. Once you've got something replicating, then it changes by modification of what's there, and not by Dembski's cartoon-model of all of the bases coming together at once. You cannot predict the probability that this little molecule will become George Bush, but you can certainly say that its descendents are virtually guaranteed to change over time as mutations occur.

But this is still based on the model that all of the components come together at random, all at once. It categorically excludes the known mechanism of evolution: modification of pre-existing stuff. I seem to recall reading that, on a clay surface, an "RNA" of only two bases in length can replicate, producing daughter molecules of two bases in length. If this is a valid model for the first replicating thingies, then Dembski's lost the game. If you have a bunch of subunits lying around in the edge-of-the-pond, down-in-a-crevice scum, and it's chemically possible for them to bond together, and any two bonded together can become the simplest self-replicating thingie, then...why, it's no longer improbable. It becomes pretty darned likely.Jester wrote:I understand and agree with this, though I do not yet believe that the basic stance of the ID people is all that far off. The same arguments could be made (with less, but still attention worthy strength) for the earliest, least effective structures of life.

...

but his claim here references to the issue of the creation of the original codes, not the preservation of it.

Therefore, Dembski has to argue against a false model, in which complex sequences would magically come together all at once. Since there's no known means of making this magic happen, we fall back on traditional magic--god.

I'd be very disappointed in her if she didn't!Jester wrote:(Though, on completely unscientific grounds, I am more than willing to believe that the creator has a sense of humor).

Panza llena, corazon contento

- Jester

- Prodigy

- Posts: 4214

- Joined: Sun May 07, 2006 2:36 pm

- Location: Seoul, South Korea

- Been thanked: 1 time

- Contact:

Post #86

Actually, I feel that I understand the opposite. Macroevolution has produced phenotypes that are not explained through a gradual microevolution process. There are many complex biological structures and systems with interdependent parts, meaning that (while there must be a scientific explanation) microevolution principals cannot cover the development of such things, as the transitory steps would be useless or (in some cases) deeply harmful mutations.goat wrote:You don't seem to understand that 'macroevolution' is merely the accumunlation of a whole bunch of smaller changes. The key here is that mutations are accumulative. Over time, there are more and more changes in populations, and different set of allees will become dominate. This explains all the diversity we have for life. You might reject that evidence, but it the evidence is quite strong never the less.

- Jester

- Prodigy

- Posts: 4214

- Joined: Sun May 07, 2006 2:36 pm

- Location: Seoul, South Korea

- Been thanked: 1 time

- Contact:

Post #87

Yeah, this seems very reasonable if not perfectly true.Jose wrote:If we look historically, however, it may help. Evolutionary theory grew out of Natural Theology--the idea that if we catalog everything on Earth, we can better recognize the glory of god. It turned out that the more people learned, the more they found that was at odds with the simple interpretation of Genesis...and eventually, evolution was proposed to explain the data. There was resistance, but in the end, scientists were forced by the weight of the evidence to abandon their prior explanations and accept evolution. Unfortunately (in a way), those struggles are in the distant past, so the public tends to view evolution as a form of scientific bias rather than a principle that is so strongly confirmed that there's no need to discuss it any more.

This does make sense. But there’s always one more question, I guess. Wouldn’t this imply that the abundance of oxygen initially would have to have come from some source other than photosynthesis, however?Jose wrote:So your question is important. There was lots more UV hitting the earth before photosynthesis produced enough oxygen to build up an ozone layer. How, then, could amino acids and nucleotides get produced, and why weren't they all destroyed?

The short answer is: every rock has an underside. A longer answer is: a place like Yellowstone has lots of cracks and fissures, and lots of sulfur, and lots of places where warm water evaporates to leave concentrated goo from whatever was dissolved in it. The appropriate image to visualize for a chemical origin of life is probably something like the edge of a pool, with perhaps a bit of sulfur around, and some cracks and fissures that UV light cannot penetrate. (I mention sulfur simply because some micrororganisms use H2S rather than H2O as a source of electrons--"chemiautotrophs" rather than "photoautotrophs." A chemical energy source is likely to pre-date the development of a means of harvesting light energy in normal photosynthesis. So far as I know, this is the current thinking.

Good, I’d hoped you were enjoying this as much as I.Jose wrote:Oh Boy!...this is the fun part.

Thank you, that makes much more sense than what I’d been told. The same basic statement goes for the remainder of the explanations.Jose wrote:The data show there is no rule concerning complexity. Species introduced to islands, and then tracked over time, are just as likely to lose complexity as to gain it. Steve Gould explored this issue in detail in Full House, in an amusing mix of biology and baseball.

Yeah, we do tend to forget how much we do not know (That’s one of the more odd sentences I’ve ever written.). I suppose the fossil record is the only reasonable way to set up a timeline.Jose wrote:But I can't answer your second question, other than to say "I guess it took as long as it took." There are too many unknowns. For example, if the asteroid hadn't crashed into Chixulub, wiping out the dinosaurs, we'd probably still be little furtive shrew-like critters trying to avoid being eaten.

That is excellent advice. I’ll have to remember that one.Jose wrote:Fortunately, the bias can enter into the interpretation, but not into the data themselves. Data are really the only "facts" in science. We observe XXX. What do we make of it? The trick is to examine the data first, come to your own conclusion, and then check to see if the authors got it right.Jester wrote:My trouble is that I have come to believe that I will always be reading one bias or another. It sometimes feels that sifting through the biases is the only thing harder than sifting through the data.

I would wholeheartedly agree that this explains many of the situations. I am not sure of some others. It seems that there should, ultimately, emerge a different explanation for this. My example of the caterpillar was due to the fact that it seems particularly puzzling. It possesses the ability to turn to jelly inside the cocoon, and reform as a butterfly. I personally feel that it is a safe assumption that the final scientific explanation for this will not rest primarily on microevolution principals.Jose wrote:This assumes a particular transitory phase. The proper question is "what was the transitory phase?" This question makes sense only in the context of the next question, "what was the ecological context in which these animals/plants lived?" Something half-way between a fin and a foot seems problematical if we think of your average shark walking up onto the beach. But it's not problematical when we know the ecological context from the other fossils found in the same locale, and realize that this guy lived in a swamp. If he used his fin/foot transitional structure to push against mangrove roots while still in the water, now there's a very good use for it.

That, I am completely willing to believe (I’ll have to read the more lengthy explanations on that one).Jose wrote:So, the scientific reasoning is not circular. What seems circular is the simplified description that is passed around in general conversation.

Absolutely.Jose wrote:In this sense, I think the Dawkins types do their science a disservice. If he would stick to what we can really conclude, he'd be better. That is, we can conclude that we can explain the natural world through natural processes, and there is no absolute need for gods. Of course, there may be gods, but we have no data that allow us to say anything about them. Or, there may not be gods, but without data, we can't really tell.

The more I study science, the less I trust anyone who makes bold statements. “We’re looking into that” seems to be part of any valid answer about a specific situation. I suppose I’ll just have to be satisfied with that.Jose wrote:The short answer: we don't know. I'll argue that nucleic acid components, even now, "tend to hydrolyze," and that RNA molecules are particularly prone to hydrolysis. By this logic, RNA shouldn't exist now, either. And, while there are chemicals that might react preferentially with nucleotides, it's rather hard to argue that these chemicals were always present with nucleotides. We know that different things are distributed unevenly around the earth now; why would they have been perfectly uniform then? Sure, one can argue that life was unlikely, but then, the probability is also vanishingly low that anyone would ever get the precise combination of my Mom's alleles and my Dad's alleles that I got. Yet, it did happen, likely or not.

Yeah, I am forced to admit that the matter of alternate possibilities seems to be an unanswerable question.Jose wrote:Needless to say, any life that arises in particular conditions will be suited to those conditions. But, are there alternate possibilities? There are probably bazillions. There are an infinite number of possible amino acids; life happened to choose only 20. There are lots and lots of nucleotides; life happened to choose only 4…

My hobby, however, is sci-fi writing. So I suppose the personal upshot for me is that this gives me quite a few “what if”s to work with.

That does make sense, I’ll keep that in mind when I look over the information again.Jose wrote:This relates to the Cambrian phyla, by the way. Once those primitive forms had arisen, they restricted the development of their descendents. There were enough of 'em, and they were successful enough, that new things tended to be out-competed by the guys already there.

That does explain some of my question, though I’m still not sure. I feel that RNA could not have been developed more or less randomly, even with self-replications. I’d be more willing to believe that it was formed based on outside pressures- a very simple form of a biological substance that influenced its design over time. (Of course, that’s a personal guess, not science).Jose wrote:If we think of a simple RNA, we can make some sense of this. Suppose it's a short sequence that can fold back on itself to make a little hairpin. This might enable it to form a template for replicating itself. But, it would be sloppy, and might put in an extra base. On the next round of replication, the extra base would be copied, and we'd have a hairpin that's one base-pair longer. It would be a little bit more stable. Mistakes that leave out a base would be less stable, and might not replicate as well.

Two molecules that have the ability to interact with each other can also form hybrids, or double-length molecules, or molecules with extra hairpins. The catalytic RNAs that we know all have multiple hairpins, so this seems like something that is likely to have happened.

The point is, a very simple self-replicating molecule (in a crevice, away from UV, with silica grains to act as catalyst) can grow into a more complex molecule. Once you've got something replicating, then it changes by modification of what's there, and not by Dembski's cartoon-model of all of the bases coming together at once. You cannot predict the probability that this little molecule will become George Bush, but you can certainly say that its descendents are virtually guaranteed to change over time as mutations occur.

Perhaps I am somehow misunderstanding the ID claim, but I am left with the thought that the probability argument works equally well against the idea that these were a collection of changes acquired over long periods of time. It does seem to stand to reason that there must be some mechanism that brought changes this specifically (whether slowly or quickly). I see the trouble with calling that mechanism an Intelligent Designer, but feel that self-replication without some guiding force does not answer the dilemma. I suppose the real question is: can we apply principals of biological evolution to these earliest molecules, or do we need to seek some other explanation?Jose wrote:But this is still based on the model that all of the components come together at random, all at once.

I would be disappointed as well (but don’t think I will be).Jose wrote:I'd be very disappointed in her if she didn't!Jester wrote:(Though, on completely unscientific grounds, I am more than willing to believe that the creator has a sense of humor).

And so long as you bring up the gender of God issue, how can I not comment?

I’ve always personally wondered why most adherents of my religion are so adamant on the gender of a God which has both male and female names in the Bible and, more to the point, doesn’t have a body (as long as we're discussing biology, that's a problem for thier argument).

- Goat

- Site Supporter

- Posts: 24999

- Joined: Fri Jul 21, 2006 6:09 pm

- Has thanked: 25 times

- Been thanked: 207 times

Post #88

Name the ones you are talking about. SHow them. Let's examine the ones you are saying. Yes, there are biological structures with interdependant parts, but thatJester wrote:Actually, I feel that I understand the opposite. Macroevolution has produced phenotypes that are not explained through a gradual microevolution process. There are many complex biological structures and systems with interdependent parts, meaning that (while there must be a scientific explanation) microevolution principals cannot cover the development of such things, as the transitory steps would be useless or (in some cases) deeply harmful mutations.goat wrote:You don't seem to understand that 'macroevolution' is merely the accumunlation of a whole bunch of smaller changes. The key here is that mutations are accumulative. Over time, there are more and more changes in populations, and different set of allees will become dominate. This explains all the diversity we have for life. You might reject that evidence, but it the evidence is quite strong never the less.

is certainly no problem, variation/mutation and ns would reuse structures that are there, not invent them out of thin air.

- Jester

- Prodigy

- Posts: 4214

- Joined: Sun May 07, 2006 2:36 pm

- Location: Seoul, South Korea

- Been thanked: 1 time

- Contact:

Post #89

Okay, here goes. (Just one example though)goat wrote:Name the ones you are talking about. SHow them. Let's examine the ones you are saying. Yes, there are biological structures with interdependant parts, but that

is certainly no problem, variation/mutation and ns would reuse structures that are there, not invent them out of thin air.

“What type of biological system could not be formed by ‘numerous, successive, slight modifications’?

Well, for starters, a system that is irreducibly complex. By irreducibly complex I mean a single system composed of several well-matched, interacting parts that contribute to the basic function, wherein the removal of any one of the parts causes the system to effectively cease functioning. An irreducibly complex system cannot be produced directly (that is, by continuously improving the initial function, which continues to work by the same mechanism) by slight, successive modifications of a precursor system, because any precursor to an irreducibly complex system that is missing a part is by definition nonfunctional. An irreducibly complex biological system, if there is such a thing, would be a powerful challenge to Darwinian evolution. Since natural selection can only choose systems that are already working, then if a biological system cannot be produced gradually it would have to arise as an integrated unit, in one fell swoop, for natural selection to have anything to act on.”

-Michael J. Behe “Darwin’s Black Box” pg 39 (the example that follows is paraphrased from the same book).

The specific example of this is the Cilium (the whip-like structure which is used by some single-celled organisms which is used to propel the cell through liquid.)

Ciliary motion requires microtubules; otherwise, there would be no strands to move as propulsion. Additionally it requires a motor, or else the microtubules of the cilium would lie stiff and motionless. Furthermore, it requires linkers to tug on neighboring strands, converting the sliding motion into a bending motion, and preventing the structure from falling apart. All of these parts are required to perform one function: ciliary motion. Just as a mousetrap does not work unless all of its constituent parts are present, ciliary motion simply does not exist in the absence of microtubules, connectors, and motors. Therefore we can conclude that the cilium is irreducibly complex.

To rule out evolution as the proper scientific explanation, however, we must also rule out the possibility of an indirect route of evolution. That is to say that we must rule out the possibility that these separate structures were created for different functional purposes and brought together in a functional way as a believably small evolutionary step.

Microtubules occur in many cells and are usually used as mere structureal supports. Motor proteins are involved in other cell functions. The motor proteins are known to travel along microtubules, and a protein motor may have acquired the ability to push on two neighboring microtubules. (making a basic motion that could have evolved gradually into a cilium)

The trouble with this explanation is that a protein indiscriminately attached to microtubules would disrupt the cell’s shape. This accidental structure, even were it at the surface of the cell, would still lack the ability to propel the cell in any case. Microtubules, other than in the case of an irreducibly complex system, do not exist outside of the cell membrane. Nor can a single protein motor attached between two microtubules create motion even if they protrude beyond the cellular membrane (which is allready an interdependent system), due to the fact that a single motor protien is not large enough to do more than pull the two together.

- Goat

- Site Supporter

- Posts: 24999

- Joined: Fri Jul 21, 2006 6:09 pm

- Has thanked: 25 times

- Been thanked: 207 times

Post #90

Ah yes.. you do realise that Irredibubly complex systems CAN evolve naturally. They have even come up with an experiment that can show an IRC systemJester wrote:Okay, here goes. (Just one example though)goat wrote:Name the ones you are talking about. SHow them. Let's examine the ones you are saying. Yes, there are biological structures with interdependant parts, but that

is certainly no problem, variation/mutation and ns would reuse structures that are there, not invent them out of thin air.

“What type of biological system could not be formed by ‘numerous, successive, slight modifications’?

Well, for starters, a system that is irreducibly complex. By irreducibly complex I mean a single system composed of several well-matched, interacting parts that contribute to the basic function, wherein the removal of any one of the parts causes the system to effectively cease functioning. An irreducibly complex system cannot be produced directly (that is, by continuously improving the initial function, which continues to work by the same mechanism) by slight, successive modifications of a precursor system, because any precursor to an irreducibly complex system that is missing a part is by definition nonfunctional. An irreducibly complex biological system, if there is such a thing, would be a powerful challenge to Darwinian evolution. Since natural selection can only choose systems that are already working, then if a biological system cannot be produced gradually it would have to arise as an integrated unit, in one fell swoop, for natural selection to have anything to act on.”

-Michael J. Behe “Darwin’s Black Box” pg 39 (the example that follows is paraphrased from the same book).

The specific example of this is the Cilium (the whip-like structure which is used by some single-celled organisms which is used to propel the cell through liquid.)

Ciliary motion requires microtubules; otherwise, there would be no strands to move as propulsion. Additionally it requires a motor, or else the microtubules of the cilium would lie stiff and motionless. Furthermore, it requires linkers to tug on neighboring strands, converting the sliding motion into a bending motion, and preventing the structure from falling apart. All of these parts are required to perform one function: ciliary motion. Just as a mousetrap does not work unless all of its constituent parts are present, ciliary motion simply does not exist in the absence of microtubules, connectors, and motors. Therefore we can conclude that the cilium is irreducibly complex.

To rule out evolution as the proper scientific explanation, however, we must also rule out the possibility of an indirect route of evolution. That is to say that we must rule out the possibility that these separate structures were created for different functional purposes and brought together in a functional way as a believably small evolutionary step.

Microtubules occur in many cells and are usually used as mere structureal supports. Motor proteins are involved in other cell functions. The motor proteins are known to travel along microtubules, and a protein motor may have acquired the ability to push on two neighboring microtubules. (making a basic motion that could have evolved gradually into a cilium)

The trouble with this explanation is that a protein indiscriminately attached to microtubules would disrupt the cell’s shape. This accidental structure, even were it at the surface of the cell, would still lack the ability to propel the cell in any case. Microtubules, other than in the case of an irreducibly complex system, do not exist outside of the cell membrane. Nor can a single protein motor attached between two microtubules create motion even if they protrude beyond the cellular membrane (which is allready an interdependent system), due to the fact that a single motor protien is not large enough to do more than pull the two together.

evolving in the test tube at wil.

As for the Cillum, the answer to that was discovered even before Behe's "Black Box" was published.

This has even been put in the 'creationist claims' section of Talk origins

http://www.talkorigins.org/indexcc/CB/CB200_1.html